|

The humans live in time but our Enemy [God] destines them to eternity. He therefore, I believe, wants them to attend chiefly to two things, to eternity itself, and to that point of time which they call the Present. For the Present is the point at which time touches eternity…. He would therefore have them continually concerned either with eternity (which means being concerned with Him) or with the Present — either meditating on their eternal union with, or separation from, Himself, or else obeying the present voice of conscience, bearing the present cross, receiving the present grace, giving thanks for the present pleasure.

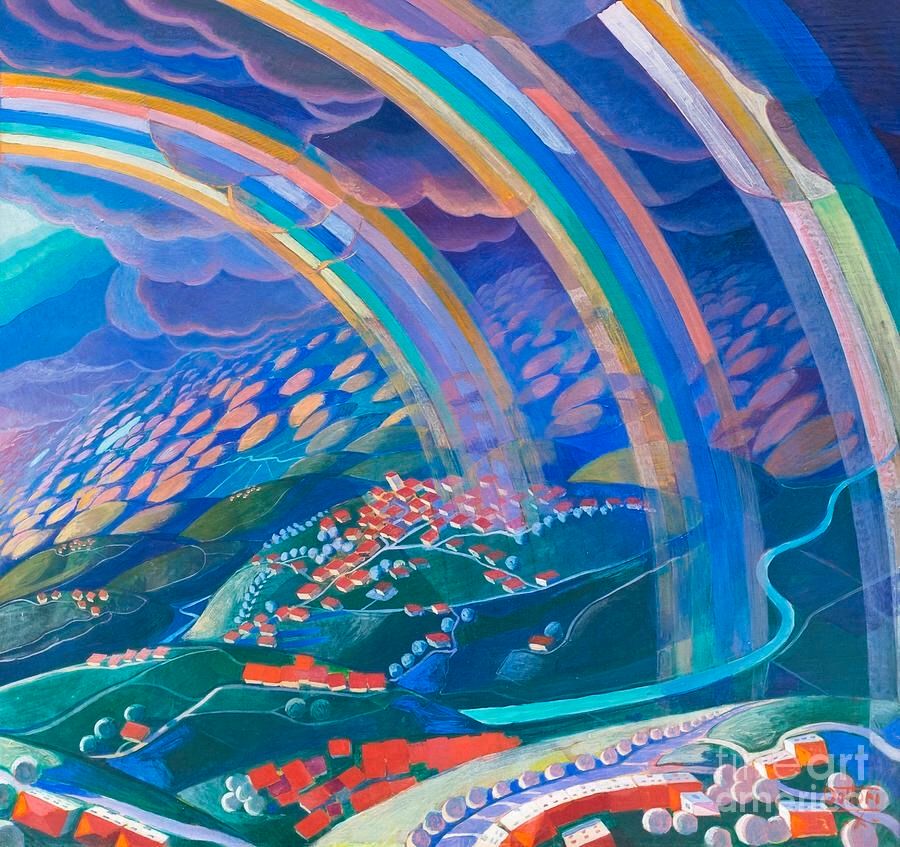

Our business is to get them away from the eternal, and from the Present. With this in view, we sometimes tempt a human (say a widow or a scholar) to live in the Past. But… it is far better to make them live in the Future. Biological necessity makes all their passions point in that direction already, so that thought about the Future inflames hope and fear. Also, it is unknown to them, so that in making them think about it we make them think of unrealities. In a word, the Future is, of all things, the thing least like eternity. It is the most completely temporal part of time — for the Past is frozen and no longer flows, and the Present is all lit up with eternal rays…. Hence nearly all vices are rooted in the future. Gratitude looks to the past and love to the present; fear, avarice, lust, and ambition look ahead…. To be sure, the Enemy wants men to think of the Future too — just so much as is necessary for now planning the acts of justice or charity which will probably be their duty tomorrow. The duty of planning the morrow’s work is today’s duty; though its material is borrowed from the future, the duty, like all duties, is in the Present. This is not straw splitting. He does not want men to give the Future their hearts, to place their treasure in it. We do. His ideal is a man who, having worked all day for the good of posterity (if that is his vocation), washes his mind of the whole subject, commits the issue to Heaven, and returns at once to the patience or gratitude demanded by the moment that is passing over him. But we want a man hag-ridden by the Future — haunted by visions of an imminent heaven or hell upon earth — ready to break the Enemy’s commands in the present if by so doing we make him think he can attain the one or avert the other — dependent for his faith on the success or failure of schemes whose end he will not live to see. We want a whole race perpetually in pursuit of the rainbow’s end, never honest, nor kind, nor happy now, but always using as mere fuel wherewith to heap the altar of the future every real gift which is offered them in the Present.[1] Such are the words of infernal “wisdom” dripping from the pen of C.S. Lewis’ master tempter Screwtape to his underling Wormwood. Lewis’ diabolical protagonist (or antagonist) brings up that there are two things God wants us as creatures to chiefly attend to eternity and the present. There is deep wisdom in this. It is a truism that one of the central ways the principalities and powers try to destroy our souls is by enslaving us to futurism and materialism. They want us to live our existence in a time that has yet to be in the hopes of aggravating our anxieties and ingratitude. By whatever means necessary their goal is to ensure we do not spend an adequate amount of time being reflective, contented, or joyous in the ordinary nowness of our lives. As Lewis says, they want us “hag-ridden by the Future.” Unfortunately, far too often, the dark forces against us tend to succeed in making us time travelers. They get us to be people who are located in the present but not living in it – instead, we are thousands of miles away inhabiting our pasts and futures. This is why, for many of us, we are a people full of insecurities, fears, unforgiveness, and restlessness. The French mathematician and Christian thinker Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) put his finger on the pulse of this mode of existence when he wrote in his day, “We never keep to the present. We recall the past; we anticipate the future as if we found it too slow in coming and were trying to hurry it up, or we recall the past as if to stay its too rapid flight. We are so unwise that we wander about in times that do not belong to us, and do not think of the only one that does; so vain that we dream of time that are not and blindly flee the only one that is. The fact is that the present usually hurts. We thrust it out of sight because it distresses us, and if we find it enjoyable, we are sorry to see it slip away. We try to give it the support of the future, and think how we are going to arrange things over which we have no control for a time we can never be sure of reaching.” “Let each of us examine his thoughts; he will find them wholly concerned with the past or the future. We almost never think of the present, and if we do think of it, it is only to see what light it throws on our plans for the future. The present is never our end. The past and the present are our means, the future alone our end. Thus we never actually live, but hope to live, and since we are always planning how to be happy, it is inevitable that we should never be so.”[2] The last sentence deserves to be repeated, “Thus we never actually live but hope to live, and since we are always planning how to be happy, it is inevitable that we should never be so.” In short, Pascal is bringing to light one of the malaises of our post-modern existence: we always plan for happiness and never achieve it. Our lives are spent seeking for joy in a realm of temporal existence we are not living in yet (namely the future). It is the bane of the “One-Day-ism” syndrome. This is where we consciously or subconsciously tend to think that the future is where our happiness, security, and contentment reside. True happiness, we think, lies at the weekend, or it's when we will meet that special someone, or when that new job or promotion comes, or when we can cash into that retirement plan, or when we can catch that perfect getaway we’ve been saving up for. Don’t misunderstand. “One-days” are not wrong or bad – they are a constant feature of hope itself. We can and should prepare, store up, and even look forward to that which is not yet. The problem comes when we assign our “one-days” the unrealistic expectation that they are without question the remedy to satiate our restless hearts. Before our one-days “whisk us away” we tend to accustom ourselves to plodding around in our piecemeal lives of mediocrity, being filled with anxiety, dissatisfaction, unforgiveness, and boredom. As a result, we live less fulfilled lives and remain spiritual anemic – and we’re very good about convincing ourselves that we aren’t when in fact we are. The problem is we are not guaranteed one-days (James 4:13). Because of this stark realization, we need to have a transvaluation of our values and a realignment of our worldviews. Part of this comes from seeing our present differently, as Lewis points out through Screwtape. We need to begin to see the world as permeated with the rays of eternity, as a realm we can occupy with joy and contentment, and peace. FAITH IS IN THE PRESENT TENSE In affirming that God wants us to think of the present Lewis is not meaning we must denounce remembrance, expectation, or preparedness in our lives (for these are good and biblical), rather he is bringing to our awareness the need to soak in the present with joy, patience, and appreciation by coming to a mindfulness of the eternal that saturates it. He is reminding us that the power of faith lies now in its capacity to be merely future-directed but in its abiding transformative nowness to ignite our character and perspective of our everyday experiences (both good and bad). A.W. Tozer (1897-1963) put it this way, “Faith in Christ is not an act to be done and gotten over with as one might get inoculated against yellow fever or cholera. The repentant sinner's first act of believing in Christ for forgiveness and eternal life is the beginning of a continuous act of believing which lasts throughout life and for all eternity.”[3] What Tozer is getting at (as well as Pascal and Lewis) is as biblical as it is practical: faith is an active state of existence that we are to live in. Faith is not just believing for but is the very act of believing in. Faith is not a belief extended into the future alone but is rooted in present reality that acknowledges God as a God of immanent withness or presence. Remember how the writer of Hebrews put it, “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (11:1) Faith is a present reality (things not seen) of the God Who is that grounds our confidence in what is not yet (things hoped for).[4] In short, you cannot have faith that God will do unless you have an active faith that God is doing. This requires an intentional awareness of the transcendent and eternal in daily life. This is why Lewis links the present with eternity so closely. Understanding the true immanence of God in our midst, that He is with us (Immanuel), that His peace and strength and joy is with us now, changes fundamentally how we see the moment we are in rather than just maintaining us for a future that is yet to be. ETERNITY IS BLEEDING THROUGH INTO THE ORDINARY The practice of “living in the present” has deep Christian roots. The Psalmist told us to cast our burdens upon the Lord that He may sustain us (Psalm 55:22), which is a present-centered promise. The Apostle Paul affirmed that our outer self is wasting away but our inner self is renewed day by day (2 Corinthians 4:16). James had said we should not worry about tomorrow because of the evanescence of life and instead should rest in God’s will (James 4:13-16). Jesus Himself said we are to be a people who pray for daily bread (Matthew 6:11) and are not to be anxious about a new day but concentrate on today (Matthew 6:34). The Biblical vision of “presentness” is not a pietistic otherworldliness of “I’ll-Fly-Away-ism”; it is not detaching ourselves from the everyday monotony and responsibilities of life, and it’s not navel-gazing or Eastern mysticism. We are being called to live in the moment but not for the moment. There is a difference. The latter is presentistic and shallow, recklessly unabandoned in wisdom or reflection. This is not what we are talking about. We are talking about a deeper reflection upon the nature of everyday experience as seen through the lens of the eternal. It is a call for us to recover the sacredness of ordinary life. To be still and know that God is God (Psalm 46:10). As one author has put it, “The aim when we practice the present is not to learn a bunch of techniques but to learn how to live and relate to God in the here and now. Practicing the present is about living for God by living with God in the real world. The best way to practice the present is to look for the reality of God’s presence in the full and sometimes disappointing realities of ordinary circumstances.”[5] Life, in all its seeming mediocrity, is emblazoned with the presence of God. Eternity is bleeding through into our ordinary lives. Are we aware of this? We serve a God who is immanent. He is present with us and in us and among us. God is in the simple and God is in the grand. God is with us and among us not just before us. Really! Stop at this moment and really think on this! As theologian Thomas Oden (1931-2016) said, “Only when one thinks of oneself as standing on the edge of either a happy or pitiable eternity does present life become meaningful and serious.”[6] We need to be serious about ordinary spirituality. We need to be a people that see God as more than a Sunday experience or a future God of some revival experience. We need to stop seeing God as merely a “one-day” fulfiller of greater spiritual growth or even material blessings. We need to stop seeing God as merely “Coming in the Clouds” at the expense of seeing Him in the cloudiness of life’s experiences. While He is the God of all those things, He is also the God of now! And by this, I do not mean a God of “gimme-gimme” instant gratification, miracles, and blessings (although He can). I am talking about becoming acutely aware of our immediate surroundings and ordinary everyday spirituality – i.e. what living the Christian life is when it’s not Sunday! I am talking about realizing that God is the God in our midst when we clean dishes, prepare a meal, stock the shelves, watch the kids, take a walk, pay the bills, or drive the car. When we begin to actively and consciously try to think upon and touch God in these moments, then their monotony begins to melt, and our anxiousness is undone and our ingratitude is thrown upon the altar of worship and thanks. In closing this post (of which I but scratched the surface of this profound topic) I leave you with an extended quote from the Christian Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) who wrote long ago about being a person who is present-minded in their faith, The one who rows a boat turns his back to the goal toward which he is working. So it is with the next day. When, with the help of the eternal, a person lives absorbed in today, he turns his back to the next day. The more he is eternally absorbed in today, the more decisively he turns his back to the next day; then he goes not see it at all…. This is the way one is turned when one rows a boat, but so also is one position when one believes…. If a person turns to the future, and especially with earthly passion, then he is most distanced from the eternal, then the next day becomes a monstrous confused figure, like that in a fairytale…. The believer is one who is present and also…a person of power…. How rare is the person who actually is contemporary with himself; ordinarily most people are apocalyptically, in theatrical illusions, hundreds of thousands of miles ahead of themselves, or several generations ahead of themselves in feelings, in delusions, in intentions, in resolutions, in wishes, in longings. But the believer (the one present) is in the highest sense contemporary with himself. To be totally contemporary with oneself today with the help of the eternal is also formative and generative; it is the gaining of eternity. There certainly was never any contemporary event or any most honored contemporary as great as eternity…. To live in this way, to fill up the day today with the eternal and not with the next day, the Christian has learned or is learning (for the Christian is always a learner) from the prototype [Christ Himself]. How did he conduct himself in living without care about the next day – he who from the first moment he made his appearance as a teacher knew how his life would end, that the next day would be his crucifixion, knew it while the people were jubilantly hailing him as king (what bitter knowledge at that very moment!), knew it when they were shouting hosannas during his entry into Jerusalem, knew that they would be shouting ‘Crucify him!’ and that it was for this that he was entering Jerusalem – he who bore the enormous weight of this superhuman knowledge every day – how did he conduct himself in living without care about the next day?... How did he conduct himself in living without care about the next day – he who was indeed not unacquainted with suffering of this anxiety or with any other human suffering, he who groaned in an outburst of pain, ‘Would that the hour had already come’? … How did he manage?.... [That answer is] He had the eternal with him in his today – therefore the next day had no power over him, it did not exist to him. It has no power over him before it came, and when it came and was the today, it has no other power over him than what was his Father’s will, to which he, eternally free, had consented and to which he obediently submitted.”[7] ________________________________________________________ [1] C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters in Signature Classics (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2003), pg. 227-229 [2] Blaise Pascal as quoted in Peter Kreeft, Christianity for Modern Pagans (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 1993) pg. 74 [3] https://www.cmalliance.org/devotions/tozer?id=457 [4] Faith is not merely future directed but is a present active style of living that resides in the nowness of God’s promises, grace, and truth. Consider some sources on this: J.I. Packer, “Faith” entry in Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, 2nd ed, ed. Walter A. Elwell (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2001) pg. 431-434; David L. Allen, Hebrews, The New American Commentary (Nashville, TN: B & H Publishing, 2010) pg. 542-543 [5] John Koessler, Practicing the Present: The Neglected Art of Living in the Now (Chicago, IL: Moody Publishers, 2019) pg. 210 [6] Thomas Oden, John Wesley’s Scriptural Christianity: A Plain Exposition of His Teaching on Christian Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994), pg. 30 [7] Søren Kierkegaard, Christian Discourses; The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress, ed. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997) pg. 73-76

0 Comments

|

AuthorMichael H. Erskine is a high school Social Studies Teacher, has an M.A. in History & School Administration, serves as a Bible teacher in the local church, and is happily married to his beautiful wife Amanda. aRCHIVES

November 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed